The New Equalisers - drones and technology in war

In the 1840s, Samuel Colt's revolver earned the slogan "God made man but Samuel Colt made them equal." Today's drones are repeating that revolution.

War has been commoditised. What was once the exclusive domain of superpowers can now be conducted by anyone with a few hundred pounds and the right knowledge. The proof lies in the smoking ruins of Russian airbases and Iranian nuclear facilities, destroyed not by billion-dollar weapons systems, but commercial drones that anyone can buy online.

Let's be clear about what happened.

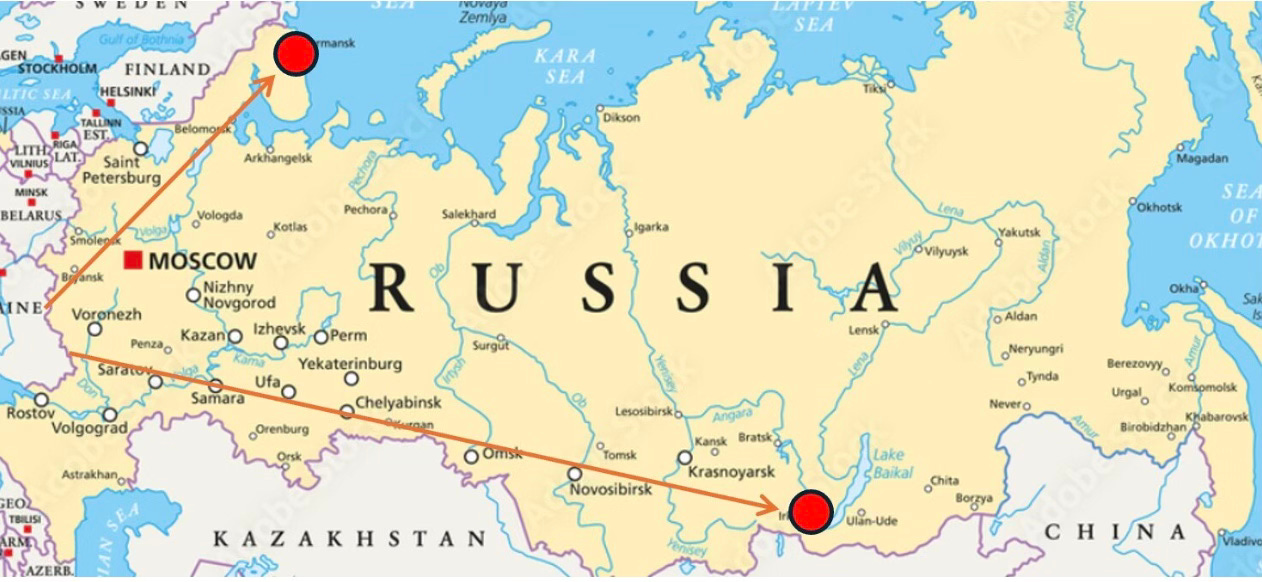

In Russia, Ukrainian operators guided 117 drones across five time zones to destroy targets 4,300 kilometres away in what became known as Operation Spiderweb. Satellite images of Belaya Air Base in Irkutsk showed at least seven Tu-95 "Bear" bombers and four Tu-22M3 "Backfire" aircraft destroyed. Soviet-era warplanes that brought death to Ukrainian cities and threatened NATO with nuclear annihilation now lay useless and irreparable.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, Israel conducted Operation Rising Lion, setting up a drone facility near Tehran and manufacturing weapons on enemy territory. They struck air defences and missile launchers, allowing warplanes to destroy nuclear targets at Natanz, Arak, Khorramabad, and Parchin, while killing regime commanders and nuclear scientists who had engineered nuclear blackmail in secret.

Together, these operations demonstrated something profound: the tools of strategic warfare are no longer exclusive. At the heart of these missions was not the exquisite but the basic; not exceptional, expensive, and unique systems, but the kind of drone you can buy in bulk and adapt to carry explosives.

This shift echoes a historic parallel.

In the 1840s, Samuel Colt's revolver earned the slogan "God made man but Samuel Colt made them equal." The weapon was so easy to use that physical strength and training no longer mattered. Anyone could win. Today's commercial drones have achieved the same democratisation, but on a strategic scale.

The mathematics of this transformation are staggering. In Afghanistan, each NATO soldier cost nearly a million dollars to maintain in-country, while insurgents costing tens of thousands of dollars were killing them. A ratio of around 50:1. But drone warfare has shattered even these imbalances. Russia's bombers cost an estimated £250 million each to replace, while the Ukrainian drones cost only around £500. That's a ratio of 500,000:1, ten thousand times greater than the Afghanistan disparity.

Colt’s revolver was so easy to use that physical strength and training no longer mattered. Anyone could win. Today's drones have achieved the same democratisation, but on a strategic scale.

This economic revolution means huge budgets provide no advantage if sophisticated systems can be destroyed by ordinary ones. The technological superiority, and range, that we have relied on for decades is eroding rapidly.

For China, these operations delivered two stark warnings. First, they agreed to support Russia's war abroad, not bring it home, but the Irkutsk airbase lies uncomfortably close, only 300 kilometres from their border. Second, truck-mounted drone attacks challenge even the most intrusive surveillance state. It would be impossible to search the 33 million trucks carrying traded goods across China. Even in Xinjiang, where the communist regime's monitoring of Uyghurs and nuclear missile silos is most intense, this capability raises serious concerns.

The pattern is spreading globally. In 2024, Pakistan deployed 300–400 drones against India in the first large-scale drone warfare between nuclear powers. Across Africa, conflicts now feature Turkish drones as standard equipment. Worldwide, groups are turning to commercial platforms for increasingly sophisticated attacks.

Kyiv proved you don't need Israel's F-35s to neutralise nuclear weapons capability. Careful planning and cheap equipment can achieve the same result.

China has already got a decisive edge in this new paradigm. It is the only state with the industrial capacity to scale this form of warfare while integrating AI-powered targeting systems. Chinese military doctrine explicitly includes drone swarms designed to overwhelm air defences, with the ability to develop and deploy these systems at unprecedented scale.

The strategic advantage runs deeper: Chinese manufacturers control 90 percent of the global commercial drone market, providing the essential components for this democratized warfare. While Western nations maintain advantages in other military domains, the learning curve is accelerating rapidly. Knowledge spreads easily through digital networks, and traditional export controls become meaningless when critical technology can be purchased online or transmitted as data files.

The implications extend far beyond distant battlefields. Russian agents have already targeted dissidents in Salisbury and London, and other groups have sabotaged aircraft at RAF Brize Norton and factories producing equipment for Ukraine. Britain itself is now within range of our enemies, and we're witnessing the first successful operations breaking through our defences.

The next drone attack may not merely disrupt an airport or threaten a stadium, but could target our nuclear supply chain, military bases, or critical infrastructure once thought protected by distance and layered defences. It won't be long before groups like the Houthis learn from Ukrainian innovations to hunt naval fleets from land, making their waters as hostile to others as the Black Sea has become to Russian ships.

This transformation extends beyond unmanned aircraft. Cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, influence operations, and even space-based assets once exclusive to superpowers are now accessible to determined groups with modest budgets. The question is no longer who can afford to play in the strategic arena, but who can adapt fastest to its new rules.

We face the same challenge as French knights at Agincourt encountering English longbows. Technological change has fundamentally altered the balance of power, and traditional advantages may prove irrelevant.

Every ship and military base will need layered defences against small, low-profile threats that were once too expensive to counter except at the most vital sites. Conventional air and ground defences struggle against these targets, requiring new approaches to protection.

Electronic warfare capabilities must expand beyond military applications to protect civilian infrastructure. States must also defend against information operations conducted from increasingly accessible platforms, while securing AI systems integrated into supply chains and countering influence campaigns that exploit social divisions.

The UK's recent Strategic Defence Review began addressing these challenges but maintained focus on large, vulnerable systems over nimble, numerous alternatives without adequate funding for either approach. The bureaucracy that built expensive, exclusive military technology is poorly suited to this commoditised landscape.

Operations Spiderweb and Rising Lion were tactically brilliant, but they've shown why we must fundamentally rethink our assumptions. Strategic surprise now emerges from the commercial, commoditised world rather than secretive military-industrial complexes.

As technology becomes a commodity, we cannot recreate the military dominance we've enjoyed through industrial might alone. Keeping ourselves safe in this new environment will challenge not just what we build, but how we think about security itself.

The shift has already happened. The question is whether we can adapt quickly enough to maintain our advantage over the militant groups and hostile states that would harm us.